Peetie Wheatstraw began recording in 1930 and was so popular that he continued to record through the Great Depression, when the number of blues records issued was drastically reduced. The blues musician Charlie Jordan introduced Wheatstraw to recording, setting him up with both Vocalion Records and Decca Records. He recorded “Tennessee Peaches Blues” in a duet with an artist called Neckbones, in August 1930. Following this first recording, Wheatstraw was especially prolific, recording 21 songs in two years, including solos like “Don’t Feel Welcome Blues,” “Strange Man Blues,” “School Days,” and “So Soon”. He made no records between March 1932 and March 1934, a period in which he perfected his mature style.

For the rest of his life, he was one of the most recorded blues singers and accompanists. His total output of 161 recorded songs was surpassed by only four prewar blues artists: Tampa Red, Big Bill Broonzy, Lonnie Johnson and Bumble Bee Slim (Amos Easton). In the clubs of St. Louis and East St. Louis his popularity was outstanding, rivalled only by that of Walter Davis. Despite references to his touring, there is little evidence that he worked outside these cities, except to make records.

For the rest of his life, he was one of the most recorded blues singers and accompanists. His total output of 161 recorded songs was surpassed by only four prewar blues artists: Tampa Red, Big Bill Broonzy, Lonnie Johnson and Bumble Bee Slim (Amos Easton). In the clubs of St. Louis and East St. Louis his popularity was outstanding, rivalled only by that of Walter Davis. Despite references to his touring, there is little evidence that he worked outside these cities, except to make records.

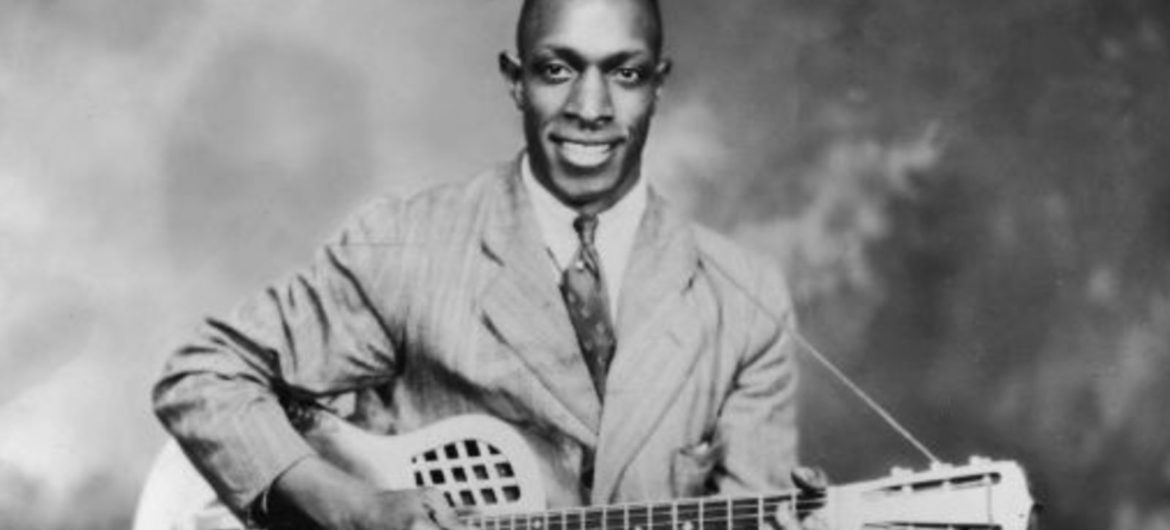

By the time Bunch reached St. Louis, he had discarded his name and crafted a new identity. The name “Peetie Wheatstraw” was described by the blues scholar Paul Oliver as one that had well-rooted folk associations. Later writers have repeated this, while reporting that many uses of the name were copied from Bunch. Elijah Wald suggested that Bunch may have been the sole source of all uses of the name. It would have been in character for Bunch to invent a name with a whimsical folkloric flavor. All but two of his records were issued under the names “Peetie Wheatstraw, the Devil’s Son-in-Law” and “Peetie Wheatstraw, the High Sheriff from Hell”. He composed several “stomps” with lyrics projecting a boastful demonic persona to match these sobriquets. His hardened attitude and egotism have given contemporary authors grounds for comparing him to modern-day rap artists. There is some evidence that the writer Ralph Ellison knew him; Ellison used the name “Peetie Wheatstraw” and aspects of the musician’s demonic persona (but no biographical facts) for a character in his novel Invisible Man.

African-American music maintains the tradition of the African “praise song”, which tells of the prowess (sexual and other) of the singer. First-person celebrations of the self provide the impetus for many of Wheatstraw’s songs, and he rang changes on this theme with confidence, humour and occasional menace. The blues singer Henry Townsend recalled that “He was a jive-type person.” The blues critic Tony Russell updated the description: “Wheatstraw constructed a macho persona that made him the spiritual ancestor of rap artists.”